There’s a saying attributed to the drummer Art Blakey: “Music washes away the dust of everyday life.” It was something he liked to say to his audiences from the bandstand, an opening invocation meant to bring listeners into a place of receptivity. But the motto has resonated through the years as a kind of mantra for jazz musicians, a confirmation that their craft and life’s work has a higher purpose and meaning. It’s a message that seems to bear more truth the longer it echoes.

This October marks 100 years since Art Blakey’s birth. And though he died in 1990 at the age of 71, the real, tangible effects of his life in jazz are still reverberating. Credit that to his role as one of the music’s great bandleaders, a figure who achieved something rare in jazz: keeping one band — The Jazz Messengers — together and active for more than 35 years. Founded in 1947 as Art Blakey’s Messengers, the group would go through several iterations — including one that was co-led by pianist Horace Silver — until 1957, when it coalesced into the format that made it famous: two, sometimes three, horn players backed by a rhythm section in which Blakey led from his throne at the drums. Under Blakey’s auspices the band would serve as a revolving door of talent; at points, its lineups would change from year to year. It would release nearly 50 studio albums and more than 20 live recordings. During this remarkable span, The Jazz Messengers would play on nearly every continent and nearly every state in America.

Any one of The Messengers’ accomplishments would be impressive in its own right. On the strength of just a handful of the group’s albums, The Messengers would have been considered a redoubtable jazz ensemble. But the most exceptional aspect of this group — and of Blakey’s legacy in general — was that almost every musician who became a Jazz Messenger (they number more than 200) has gone on to achieve great success in music, many as lifelong accompanists, more as leaders of their own prestigious groups.

Jazz has no shortage of individual heroes, but few have legacies that have grown as exponentially as Blakey’s. He is the bandleader who launched a thousand bands, the mentor whose sage advice, through a decades-long game of jazz telephone, has reached countless ears. It’s no wonder that Blakey’s maxim about the healing power of music has endured for so long. Like the music he played, it’s a message of optimism and self-empowerment. It’s a testament to the power of music to elevate the routine, to enhance reality, to make the profane seem sacred. Through his work as a bandleader and educator, through his direct role as a mentor to dozens of musicians, he ensured that the message would continue to be delivered.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDbgLJt50ss

Here, we speak with some of The Jazz Messengers’ most distinguished alumni and Blakey collaborators about his legacy as a musician and bandleader. Their anecdotes and appreciations paint a portrait of a man whose greatest contribution to jazz was that he enabled

others to contribute equally. Art had a message. These are his messengers. -

Brian Zimmerman

Sonny Rollins

The Contemporary

Sonny Rollins first recorded with Art Blakey in 1956, as part of a session for Prestige Records that also included Kenny Drew on piano. (The session was famous for including the cut “I Know,” which featured Miles Davis on piano.) Rollins, now 88, is an NEA Jazz Master and a recognized jazz icon.

In 1959, as his career was in the midst of an ascent, he took a sabbatical from music to recuperate from the physical and mental demands of performing. He entered a period of seclusion in his neighborhood on the Lower East Side, where it is said he would practice for up to 12 hours a day on the Williamsburg Bridge, emerging two years later to produce some of his finest recordings. He recalled that Art Blakey was one of the musicians who would regularly stop by the bridge to visit.

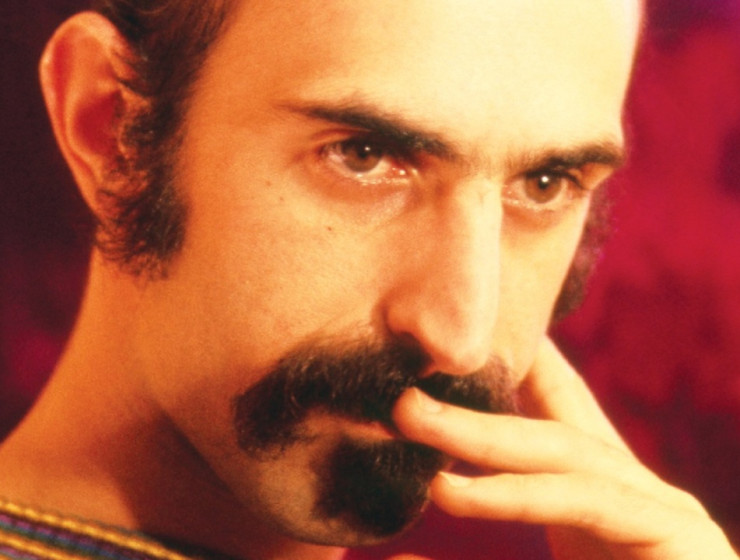

[caption id="attachment_22396" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Sonny Rollins: “Art had an elemental jazz beat, which in turn elevates everything that somebody playing jazz would do. He gave them the platform they needed to shine on their own.” Photo: John Abbott.[/caption]

Now, I was with Art before the Jazz Messengers. Art was part of my groups, so I knew him

before the teacher role. We were both coming up together, and he made some of my early recordings with me, and those recordings we made with Miles, Art was on there, too. But even before the period of the Jazz Messengers, I could tell there was something special. In the studio, I never had to worry about Art. At gigs at Birdland, I never had to worry about Art. Because the thing is, everybody could get something out of playing with Art. Every one of these cats that played in the Jazz Messengers, they had so much to gain by having Art Blakey behind them; they all benefit by that. That's why so many of them went on to make prodigious contributions to jazz. Art had an elemental jazz beat, which in turn elevates everything that somebody playing jazz would do. He gave them the platform they needed to shine on their own.

Art was serious when he needed to be, frivolous when the situation called for it. There's this one story ... just thinking about it makes me laugh. Art used to live down on 177th Street off of Lenox Avenue. We were down there one night to hang out, and there happened to be a flood in his apartment building. The rats from the basement were coming up and trying to get into Art's bathroom. So everybody took turns with a baseball bat going into the bathroom trying to knock these rats back down to the basement. The rats kept coming up, and me and Art had to keep bopping them with this baseball bat to send them back down. Like a carnival game, except it was real! (

laughs)

Art was such a presence in my musical life. He even came and visited me during my sabbatical down on the Lower East Side, just to check in on me and see how I was doing. He was really a one-of-a-kind guy. In my living room, I have four pictures on the wall: one of a Buddha-type figure from Japan, one of Louis Armstrong, one of Lester Young and one of Art Blakey.

Wayne Shorter

The Disciple

Tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter joined The Jazz Messengers in 1959, combining with trumpeter Lee Morgan to form one of the most prestigious frontlines in jazz. He would remain in the group until 1963, eventually becoming its musical director, before departing for Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet in 1964. Shorter, a 10-time Grammy winner and NEA Jazz Master, credits his experience in The Jazz Messengers with providing the foundation for his career as a bandleader, a career that saw the formation of both Weather Report — one of the most influential bands in jazz fusion — and the Wayne Shorter Quartet, which has served as an incubator for today’s leading jazz talent, including Brian Blade, John Patitucci, Danilo Perez and Esperanza Spalding. His most recent album, Emanon

, won the 2018 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Album.

[caption id="attachment_22397" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Wayne Shorter: “Art is one of the baddest, baddest drummers in the world. You don’t get that drive with just anybody in the lineup. Art had thunder and lightning. He had drama. He had consistency.” Photo: Robert Ascroft.[/caption]

I actually met Art Blakey through Lee Morgan. I was up in Canada playing with Maynard Ferguson’s band at a big exhibition with Count Basie, Ahmad Jamal and The Messengers. During one intermission, Lee Morgan came running up to me, asking if I wanted to play with the Jazz Messengers [because Hank Mobley was leaving the group]. I said, “Yeah, of course!” And so he brought me over to Art’s dressing room. Art and I shook hands that day, and Art said he was going to bring me out for the French Lick Jazz Festival in Indiana. And you know, that’s exactly what happened. Lee and I flew to Indiana in a private plane from New York City. I’ll never forget it, the pilot was an old lady, with a long dress and white hair and everything. And that’s when I knew everything is different, that this Art Blakey cat was

different.

Art is one of the baddest, baddest drummers in the world. You don’t get that drive with just anybody in the lineup. Art had thunder and lightning. He had drama. He had consistency. He had a saying, “I am the original gorilla,” trying to be all dramatic, but he had a sensitivity that would come through, too, about politics and the ways of the world.

Out on the road in Europe, one of the main things Art used to say was, “When we play on that stage, the only thing people are going to remember is our behavior.” He wanted us to be on our best behavior, because he knew the music would fall in line afterward. And whenever people would reminisce about things back home in America — like I remember somebody bringing up one of those submarine sandwiches from Philadelphia — Art would say, “Man, you don't come all the way to Europe talking about no submarine sandwiches!” We didn’t talk about music in the dressing rooms. We talked about behavior.

Years later, I got a call from John Coltrane, telling me that he was leaving Miles Davis’ group. He was offering me his place. But I had already joined The Messengers. So when Miles called me asking if I wanted to be in his band, I told him I still had five years to go with The Messengers. You see, Miles knew that I would be bringing Art’s “thing” to his group. He respected Art that much. Miles didn’t even want to follow The Messengers on stage at any of these big theaters. That’s how much he respected him.

I was asked a question recently: Where are the jazz giants today? And I was thinking that the school systems now, those are taking the place of the Art Blakeys of the world, the individual jazz giants. Musicians these days have to choose between going the popular route, meaning the institutional route, or the road less traveled, the individual route. This was what Art was telling us, the importance of the individual voice.

Joanne Brackeen

The Kindred Spirit

Joanne Brackeen was the first and only female member of The Jazz Messengers. Born in California, where she grew up learning to play piano by transcribing jazz records, she moved to New York City in 1965 to be closer to the jazz scene, gaining immediate traction in bands led by George Benson, Paul Chambers, Lee Konitz, Sonny Stitt and Woody Shaw. She joined The Messengers in 1969 and would record her first record with the group, Jazz Messengers ’70

, at the start of the next decade. In 1972 she left The Messengers to play alongside numerous other jazz icons, including Joe Henderson and Stan Getz, before emerging to lead groups of her own. To date she has recorded more than two dozen recordings as a leader and penned nearly 300 original compositions. She is now a full-time professor at Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, and a Berklee guest professor at the New School in New York City.

[caption id="attachment_22398" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Joanne Brackeen: “His music just sounded like music. I don’t really know how to explain it. It’s magical, it doesn’t even have to speak on any level. It was just there, like a ‘Hallelujah.’” Photo: Carol Friedman.[/caption]

Art and I met in 1969. I lived right around the corner from this club called Slugs’. I had four kids at the time and was living in a six-floor walk-up, so I was usually tired in the evening. But this one time I saw that Art Blakey was playing, and I just had to go hear him. So I walk in, and the group is playing, sounding great. But their piano player was just sitting there at the piano, not playing. So without even thinking, I just went up there and asked Art if it was OK if I played. And he said, “Sure.” We finished the set, he came over to me at the piano and hired me on the spot.

I don't listen to a lot of recordings, because there are not too many people whose music I love, but Art was one of them. His music just sounded like

music. I don’t really know how to explain it. It’s magical, it doesn’t even have to speak on any level. It was just

there, like a “Hallelujah.” He had a sound and that’s how he

always sounded, like an orchestra from Africa.

The first concert we did together, on tour in Asia, we’ve gotten through three tunes and suddenly Art stands up and takes the mic, and he says, “And now, ladies and gentlemen, our piano player is going to play a solo piano piece of her choosing.” And that was pretty much how I learned how to play solo piano. I mean, he was crazy, but I was as crazy as he was. That’s why we connected.

After one gig, I was in my hotel room listening to

Miles Smiles, and Art came by and just sat and listened. For the next three nights, he played

exactly and

everything that Tony Williams played on the album — note for note — on the bandstand. He had an incredible mind.

Back then, he used to label people with different nicknames. He used to call me his “adopted daughter,” which was interesting, because my father’s name was Art. I lived my whole life rarely telling people what I thought about anything, because my life was so diverse, so different from anybody else’s. That's why, when I listened to Art, everything he said sounded like he was indeed my father. It was everything I imagined having in a friend, and he saw that right away. He could see things. He was a visionary.

Bobby Watson

The New Face of the Frontline

Saxophonist Bobby Watson was born in Kansas City, Kansas, and educated at the University of Miami, but claims that he earned his “doctorate” on the road with Art Blakey. His tenure with The Messengers lasted from 1977-81, a period that saw the release of more than a dozen recordings, more than any other assemblage of the group. He would end his stint as a Messenger in the role of musical director. After his departure, Watson would go on to perform alongside other giants of jazz, including drummers Max Roach and Louis Hayes, saxophonists George Coleman and Branford Marsalis, multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers and trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. Later, with bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Victor Lewis, he would launch the band Horizons, which was modeled after Blakey’s Messengers. His most recent album, Made In America

, was released on Smoke Sessions Records in 2017. He’s currently working on another album for the label set for release later this year.

[caption id="attachment_22400" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Bobby Watson: “He got to those drums and went somewhere else. And we were either going to go with him or get left behind.” Photo: John Abbott.[/caption]

My friend Curtis [Fuller] used to have this gig in Storyville [in Boston], and one night Art came down to hear me. It happened to be Art’s birthday. He comes down, buys some champagne and sits down to listen. Next thing I know, him and Butch [Miles], who was the drummer, trade sticks and places while the music is still playing. Suddenly, I feel this change in the beat behind me. It was like going down the highway doing 60, and a big semi-truck comes up behind you and nudges the car doing 70. He took me to the men’s room by the arm after that and asked me to join The Jazz Messengers.

I was 24 years old when I joined Art’s band. He taught me how to read the audience, which in turn helped me program my set. He taught me to understand the curve of a set. He taught me how to pace my solos, how to build them, how to shape them. He also told me how to deal with the public, how to be an artist, etiquette, things like that. He taught us how to dress.

The bandstand was Art’s alter. It was his sanctuary. No matter how much went down during the day, he left all his daily trouble, all his emotions, at the edge of the bandstand. And when he walked onto that bandstand, that was sacred ground. He got to those drums and went somewhere else. And we were either going to go with him or get left behind. He may have

limped onto that stage, but once sat behind the drums, his posture would become erect; his eyes would light up. And when he'd start playing, he would uplift his own soul, make himself happy. And then he’d make everybody else feel it. Because no matter how tired or angry we were, when he got there and he just set the pace by his spirit, we just went along with it.

To this day, when I go onto the stage, that's my sanctuary and my alter. That’s sacred ground. Art taught me that.

Steve Davis

The Last Messenger

Trombonist Steve Davis was the last musician ever to be hired into Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, joining the band in 1989. He appeared on the group’s final two studio recordings, including 1990’s One For All

, for which he composed the title track. In 1997, Davis would form his own ensemble sextet, also named One For All, which used The Messengers’ aesthetic as its foundation. The group has recorded 16 albums, the most recent of which, The Third Decade

, was released on Smoke Sessions Records in 2016. Davis was educated at the Hartt School of Music at the University of Hartford, studying under another Messengers alum, Jackie McLean. In 1991, he returned to the university as a professor of music, passing down the lessons he learned on Blakey’s bandstand. Steve Davis’ most recent album, Correlations

, was released on Smoke Sessions in 2018.

[caption id="attachment_22401" align="alignleft" width="1024"]

“There were no music stands, no charts, no rehearsal. It was sink or swim. You either knew the book or you didn’t. And that was an incredible learning experience for me.”[/caption]

I was a student at the University of Hartford in the late ’80s, and one year I was back at home in Binghamton when I got a call from my old teacher Jackie McLean. He said, “Steve, call this number,” and he gave me a 212 number. He said, “Buhaina’s looking for you, man.” So I call the number. After the phone gets passed around four or five times, I finally hear Blakey’s voice. He said he needed me

that night at Sweet Basil. He says, “Can you make it?” Now, I’m in Binghamton, like three hours away from the city, and it’s the middle of the afternoon. But of course, I say, “Yes!” I had to get there somehow.

Now, Frank Lacy, the great trombonist, was still in the band. This was how Art liked to do things. He would bring someone in on the same instrument just to see what happens. I tried to keep my mouth shut and play what I could play. There were no music stands, no charts, no rehearsal. It was sink or swim. You either knew the book or you didn’t. And that was an incredible learning experience for me.

My first trip to the West Coast

ever was with The Messengers. It was a few months after I joined the band. We get to Catalina's in L.A. It's the first night. Freddie Hubbard is sitting at a table directly in front of me, because he lived out there and wanted to see his old buddy Art Blakey. I’m scared to death but thrilled at the same time. We played the first set, and everything went pretty well. We come off the bandstand and Art comes off the drums. He puts his arm around me — he didn’t show me up in front of everybody, he just pulled me aside — and whispers in my ear, “You make your statement, you build to a climax and you get the ‘bleep’ out. Simple, right?” I say, “Yeah, Art.” He says, “Well,

do it then!” And then he walked away! (

laughs)

That stayed with me, man. I could have hung my head, I could have felt sorry for myself, but no, I wasn’t feeling that way at all. It was very direct and very genuine. And I just knew that I never wanted to hear that again. But Art was always very encouraging. It wasn’t always hard, tough stuff. I wouldn’t trade those experiences for the world. Being a Jazz Messenger, I’m just so proud and honored to be part of that lineage.

Ralph Peterson

The Keeper of the Flame

Ralph Peterson was one of two drummers to perform with The Jazz Messengers, having been hand-picked by Blakey as the second drummer in the legendary bandleader’s Jazz Messenger Big Band, in which he served until Blakey’s death in 1990. Peterson’s résumé includes more than 150 albums as a sideman, with credits on albums by Michael Brecker, Roy Hargrove and former Messengers bandmates Terence Blanchard and Branford Marsalis. As a leader, he has released several albums with his band Aggregate Prime, and is now preparing to release a big band CD dedicated to Blakey, as well as a record with five other Messenger alumni in a group called The Messenger Legacy. An instructor of percussion at Berklee College of Music in Boston, Peterson’s list of students includes some of today’s top drummers in E.J. Strickland, Tyshawn Story and Justin Faulkner. His most recent album, Legacy: Alive Vol. 6 at the Side Door

, was released in July on his own Onyx Productions Music Label.

[caption id="attachment_22402" align="alignleft" width="1024"]

Ralph Peterson: “I would cut classes to follow this group around — it’s a wonder I even got my degree — but I understood that the education I was getting from watching Art couldn’t be learned in a classroom.”[/caption]

I first met Art Blakey at the Jazz Forum on Bleeker Street. [Trumpeter] Terence Blanchard and I were in college together at Rutgers, and so when he got the Jazz Messengers gig, I would start following the band. I would cut classes to follow this group around — it’s a wonder I even got my degree — but I understood that the education I was getting from watching Art couldn’t be learned in a classroom. I used to like to sit right up under him. I would go up to tables of two of people I didn't know and ask to sit there with them.

One night, I go to Mikell’s jazz club uptown and Wynton [Marsalis] is there, and he re-introduces me to Art Blakey. I got to sit in with Art that night, along with Cindy Blackman, Jeff “Tain” Watts and Marvin “Smitty” Smith. I think for my tune we played “Birdlike,” or one of the easier tunes, but I was prepared to play anything. My job was to make as good of an impression on Art as possible. But the real moment happened as Art was heading back to the bandstand. I kicked off the cadence for “The Theme,” which was how The Jazz Messengers used to close their shows. I had all the breaks, time and tempo changes, the slide into the New Orleans feel, the double-time on the bridge with the break at the end. I had it

down. Art ran with that, catting it up in front of the bandstand, like, “What am I supposed to do with this cat playing all my stuff?”

The following March — March of 1983 — he called me up to do the Boston Globe Jazz Festival with the big band, the one with two drummers. And after that, I became “the guy” people would call if they wanted to put a Blakey program together. You see, what’s unique about my relationship with Art is that I was really keen on emulating him. At my stage of development when I was a student, I was in touch with how much I

didn’t know about jazz drummers. I wasn’t looking for my own voice; I was content to be teased by the cats in New York when they called me “Baby Bu.” Because as long as I was a “Baby” version of somebody who was swinging, and that was respected, I didn’t give a shit whose “Baby” I was. I think we confuse a lot of young musicians now by robbing them of that process of

assimilation, because we don’t encourage

imitation. You gotta play some other people’s songs so that you learn your way around the instrument. That’s the process, and that was Blakey’s whole thing.

Art Blakey was one of the most important bandleaders in American music. He did it for 50 years, and the number of bandleaders that emerged from his band is astounding. And not just people who can slap their names on an album cover. I'm talking about musical conceptualists. Leaders of music and men.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cv9NSR-2DwM

This October marks 100 years since Art Blakey’s birth. And though he died in 1990 at the age of 71, the real, tangible effects of his life in jazz are still reverberating. Credit that to his role as one of the music’s great bandleaders, a figure who achieved something rare in jazz: keeping one band — The Jazz Messengers — together and active for more than 35 years. Founded in 1947 as Art Blakey’s Messengers, the group would go through several iterations — including one that was co-led by pianist Horace Silver — until 1957, when it coalesced into the format that made it famous: two, sometimes three, horn players backed by a rhythm section in which Blakey led from his throne at the drums. Under Blakey’s auspices the band would serve as a revolving door of talent; at points, its lineups would change from year to year. It would release nearly 50 studio albums and more than 20 live recordings. During this remarkable span, The Jazz Messengers would play on nearly every continent and nearly every state in America.

Any one of The Messengers’ accomplishments would be impressive in its own right. On the strength of just a handful of the group’s albums, The Messengers would have been considered a redoubtable jazz ensemble. But the most exceptional aspect of this group — and of Blakey’s legacy in general — was that almost every musician who became a Jazz Messenger (they number more than 200) has gone on to achieve great success in music, many as lifelong accompanists, more as leaders of their own prestigious groups.

Jazz has no shortage of individual heroes, but few have legacies that have grown as exponentially as Blakey’s. He is the bandleader who launched a thousand bands, the mentor whose sage advice, through a decades-long game of jazz telephone, has reached countless ears. It’s no wonder that Blakey’s maxim about the healing power of music has endured for so long. Like the music he played, it’s a message of optimism and self-empowerment. It’s a testament to the power of music to elevate the routine, to enhance reality, to make the profane seem sacred. Through his work as a bandleader and educator, through his direct role as a mentor to dozens of musicians, he ensured that the message would continue to be delivered.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDbgLJt50ss

Here, we speak with some of The Jazz Messengers’ most distinguished alumni and Blakey collaborators about his legacy as a musician and bandleader. Their anecdotes and appreciations paint a portrait of a man whose greatest contribution to jazz was that he enabled others to contribute equally. Art had a message. These are his messengers. - Brian Zimmerman

This October marks 100 years since Art Blakey’s birth. And though he died in 1990 at the age of 71, the real, tangible effects of his life in jazz are still reverberating. Credit that to his role as one of the music’s great bandleaders, a figure who achieved something rare in jazz: keeping one band — The Jazz Messengers — together and active for more than 35 years. Founded in 1947 as Art Blakey’s Messengers, the group would go through several iterations — including one that was co-led by pianist Horace Silver — until 1957, when it coalesced into the format that made it famous: two, sometimes three, horn players backed by a rhythm section in which Blakey led from his throne at the drums. Under Blakey’s auspices the band would serve as a revolving door of talent; at points, its lineups would change from year to year. It would release nearly 50 studio albums and more than 20 live recordings. During this remarkable span, The Jazz Messengers would play on nearly every continent and nearly every state in America.

Any one of The Messengers’ accomplishments would be impressive in its own right. On the strength of just a handful of the group’s albums, The Messengers would have been considered a redoubtable jazz ensemble. But the most exceptional aspect of this group — and of Blakey’s legacy in general — was that almost every musician who became a Jazz Messenger (they number more than 200) has gone on to achieve great success in music, many as lifelong accompanists, more as leaders of their own prestigious groups.

Jazz has no shortage of individual heroes, but few have legacies that have grown as exponentially as Blakey’s. He is the bandleader who launched a thousand bands, the mentor whose sage advice, through a decades-long game of jazz telephone, has reached countless ears. It’s no wonder that Blakey’s maxim about the healing power of music has endured for so long. Like the music he played, it’s a message of optimism and self-empowerment. It’s a testament to the power of music to elevate the routine, to enhance reality, to make the profane seem sacred. Through his work as a bandleader and educator, through his direct role as a mentor to dozens of musicians, he ensured that the message would continue to be delivered.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDbgLJt50ss

Here, we speak with some of The Jazz Messengers’ most distinguished alumni and Blakey collaborators about his legacy as a musician and bandleader. Their anecdotes and appreciations paint a portrait of a man whose greatest contribution to jazz was that he enabled others to contribute equally. Art had a message. These are his messengers. - Brian Zimmerman

Sonny Rollins: “Art had an elemental jazz beat, which in turn elevates everything that somebody playing jazz would do. He gave them the platform they needed to shine on their own.” Photo: John Abbott.[/caption]

Now, I was with Art before the Jazz Messengers. Art was part of my groups, so I knew him before the teacher role. We were both coming up together, and he made some of my early recordings with me, and those recordings we made with Miles, Art was on there, too. But even before the period of the Jazz Messengers, I could tell there was something special. In the studio, I never had to worry about Art. At gigs at Birdland, I never had to worry about Art. Because the thing is, everybody could get something out of playing with Art. Every one of these cats that played in the Jazz Messengers, they had so much to gain by having Art Blakey behind them; they all benefit by that. That's why so many of them went on to make prodigious contributions to jazz. Art had an elemental jazz beat, which in turn elevates everything that somebody playing jazz would do. He gave them the platform they needed to shine on their own.

Art was serious when he needed to be, frivolous when the situation called for it. There's this one story ... just thinking about it makes me laugh. Art used to live down on 177th Street off of Lenox Avenue. We were down there one night to hang out, and there happened to be a flood in his apartment building. The rats from the basement were coming up and trying to get into Art's bathroom. So everybody took turns with a baseball bat going into the bathroom trying to knock these rats back down to the basement. The rats kept coming up, and me and Art had to keep bopping them with this baseball bat to send them back down. Like a carnival game, except it was real! (laughs)

Art was such a presence in my musical life. He even came and visited me during my sabbatical down on the Lower East Side, just to check in on me and see how I was doing. He was really a one-of-a-kind guy. In my living room, I have four pictures on the wall: one of a Buddha-type figure from Japan, one of Louis Armstrong, one of Lester Young and one of Art Blakey.

Sonny Rollins: “Art had an elemental jazz beat, which in turn elevates everything that somebody playing jazz would do. He gave them the platform they needed to shine on their own.” Photo: John Abbott.[/caption]

Now, I was with Art before the Jazz Messengers. Art was part of my groups, so I knew him before the teacher role. We were both coming up together, and he made some of my early recordings with me, and those recordings we made with Miles, Art was on there, too. But even before the period of the Jazz Messengers, I could tell there was something special. In the studio, I never had to worry about Art. At gigs at Birdland, I never had to worry about Art. Because the thing is, everybody could get something out of playing with Art. Every one of these cats that played in the Jazz Messengers, they had so much to gain by having Art Blakey behind them; they all benefit by that. That's why so many of them went on to make prodigious contributions to jazz. Art had an elemental jazz beat, which in turn elevates everything that somebody playing jazz would do. He gave them the platform they needed to shine on their own.

Art was serious when he needed to be, frivolous when the situation called for it. There's this one story ... just thinking about it makes me laugh. Art used to live down on 177th Street off of Lenox Avenue. We were down there one night to hang out, and there happened to be a flood in his apartment building. The rats from the basement were coming up and trying to get into Art's bathroom. So everybody took turns with a baseball bat going into the bathroom trying to knock these rats back down to the basement. The rats kept coming up, and me and Art had to keep bopping them with this baseball bat to send them back down. Like a carnival game, except it was real! (laughs)

Art was such a presence in my musical life. He even came and visited me during my sabbatical down on the Lower East Side, just to check in on me and see how I was doing. He was really a one-of-a-kind guy. In my living room, I have four pictures on the wall: one of a Buddha-type figure from Japan, one of Louis Armstrong, one of Lester Young and one of Art Blakey.

Wayne Shorter: “Art is one of the baddest, baddest drummers in the world. You don’t get that drive with just anybody in the lineup. Art had thunder and lightning. He had drama. He had consistency.” Photo: Robert Ascroft.[/caption]

I actually met Art Blakey through Lee Morgan. I was up in Canada playing with Maynard Ferguson’s band at a big exhibition with Count Basie, Ahmad Jamal and The Messengers. During one intermission, Lee Morgan came running up to me, asking if I wanted to play with the Jazz Messengers [because Hank Mobley was leaving the group]. I said, “Yeah, of course!” And so he brought me over to Art’s dressing room. Art and I shook hands that day, and Art said he was going to bring me out for the French Lick Jazz Festival in Indiana. And you know, that’s exactly what happened. Lee and I flew to Indiana in a private plane from New York City. I’ll never forget it, the pilot was an old lady, with a long dress and white hair and everything. And that’s when I knew everything is different, that this Art Blakey cat was different.

Art is one of the baddest, baddest drummers in the world. You don’t get that drive with just anybody in the lineup. Art had thunder and lightning. He had drama. He had consistency. He had a saying, “I am the original gorilla,” trying to be all dramatic, but he had a sensitivity that would come through, too, about politics and the ways of the world.

Out on the road in Europe, one of the main things Art used to say was, “When we play on that stage, the only thing people are going to remember is our behavior.” He wanted us to be on our best behavior, because he knew the music would fall in line afterward. And whenever people would reminisce about things back home in America — like I remember somebody bringing up one of those submarine sandwiches from Philadelphia — Art would say, “Man, you don't come all the way to Europe talking about no submarine sandwiches!” We didn’t talk about music in the dressing rooms. We talked about behavior.

Years later, I got a call from John Coltrane, telling me that he was leaving Miles Davis’ group. He was offering me his place. But I had already joined The Messengers. So when Miles called me asking if I wanted to be in his band, I told him I still had five years to go with The Messengers. You see, Miles knew that I would be bringing Art’s “thing” to his group. He respected Art that much. Miles didn’t even want to follow The Messengers on stage at any of these big theaters. That’s how much he respected him.

I was asked a question recently: Where are the jazz giants today? And I was thinking that the school systems now, those are taking the place of the Art Blakeys of the world, the individual jazz giants. Musicians these days have to choose between going the popular route, meaning the institutional route, or the road less traveled, the individual route. This was what Art was telling us, the importance of the individual voice.

Wayne Shorter: “Art is one of the baddest, baddest drummers in the world. You don’t get that drive with just anybody in the lineup. Art had thunder and lightning. He had drama. He had consistency.” Photo: Robert Ascroft.[/caption]

I actually met Art Blakey through Lee Morgan. I was up in Canada playing with Maynard Ferguson’s band at a big exhibition with Count Basie, Ahmad Jamal and The Messengers. During one intermission, Lee Morgan came running up to me, asking if I wanted to play with the Jazz Messengers [because Hank Mobley was leaving the group]. I said, “Yeah, of course!” And so he brought me over to Art’s dressing room. Art and I shook hands that day, and Art said he was going to bring me out for the French Lick Jazz Festival in Indiana. And you know, that’s exactly what happened. Lee and I flew to Indiana in a private plane from New York City. I’ll never forget it, the pilot was an old lady, with a long dress and white hair and everything. And that’s when I knew everything is different, that this Art Blakey cat was different.

Art is one of the baddest, baddest drummers in the world. You don’t get that drive with just anybody in the lineup. Art had thunder and lightning. He had drama. He had consistency. He had a saying, “I am the original gorilla,” trying to be all dramatic, but he had a sensitivity that would come through, too, about politics and the ways of the world.

Out on the road in Europe, one of the main things Art used to say was, “When we play on that stage, the only thing people are going to remember is our behavior.” He wanted us to be on our best behavior, because he knew the music would fall in line afterward. And whenever people would reminisce about things back home in America — like I remember somebody bringing up one of those submarine sandwiches from Philadelphia — Art would say, “Man, you don't come all the way to Europe talking about no submarine sandwiches!” We didn’t talk about music in the dressing rooms. We talked about behavior.

Years later, I got a call from John Coltrane, telling me that he was leaving Miles Davis’ group. He was offering me his place. But I had already joined The Messengers. So when Miles called me asking if I wanted to be in his band, I told him I still had five years to go with The Messengers. You see, Miles knew that I would be bringing Art’s “thing” to his group. He respected Art that much. Miles didn’t even want to follow The Messengers on stage at any of these big theaters. That’s how much he respected him.

I was asked a question recently: Where are the jazz giants today? And I was thinking that the school systems now, those are taking the place of the Art Blakeys of the world, the individual jazz giants. Musicians these days have to choose between going the popular route, meaning the institutional route, or the road less traveled, the individual route. This was what Art was telling us, the importance of the individual voice.

Joanne Brackeen: “His music just sounded like music. I don’t really know how to explain it. It’s magical, it doesn’t even have to speak on any level. It was just there, like a ‘Hallelujah.’” Photo: Carol Friedman.[/caption]

Art and I met in 1969. I lived right around the corner from this club called Slugs’. I had four kids at the time and was living in a six-floor walk-up, so I was usually tired in the evening. But this one time I saw that Art Blakey was playing, and I just had to go hear him. So I walk in, and the group is playing, sounding great. But their piano player was just sitting there at the piano, not playing. So without even thinking, I just went up there and asked Art if it was OK if I played. And he said, “Sure.” We finished the set, he came over to me at the piano and hired me on the spot.

I don't listen to a lot of recordings, because there are not too many people whose music I love, but Art was one of them. His music just sounded like music. I don’t really know how to explain it. It’s magical, it doesn’t even have to speak on any level. It was just there, like a “Hallelujah.” He had a sound and that’s how he always sounded, like an orchestra from Africa.

The first concert we did together, on tour in Asia, we’ve gotten through three tunes and suddenly Art stands up and takes the mic, and he says, “And now, ladies and gentlemen, our piano player is going to play a solo piano piece of her choosing.” And that was pretty much how I learned how to play solo piano. I mean, he was crazy, but I was as crazy as he was. That’s why we connected.

After one gig, I was in my hotel room listening to Miles Smiles, and Art came by and just sat and listened. For the next three nights, he played exactly and everything that Tony Williams played on the album — note for note — on the bandstand. He had an incredible mind.

Back then, he used to label people with different nicknames. He used to call me his “adopted daughter,” which was interesting, because my father’s name was Art. I lived my whole life rarely telling people what I thought about anything, because my life was so diverse, so different from anybody else’s. That's why, when I listened to Art, everything he said sounded like he was indeed my father. It was everything I imagined having in a friend, and he saw that right away. He could see things. He was a visionary.

Joanne Brackeen: “His music just sounded like music. I don’t really know how to explain it. It’s magical, it doesn’t even have to speak on any level. It was just there, like a ‘Hallelujah.’” Photo: Carol Friedman.[/caption]

Art and I met in 1969. I lived right around the corner from this club called Slugs’. I had four kids at the time and was living in a six-floor walk-up, so I was usually tired in the evening. But this one time I saw that Art Blakey was playing, and I just had to go hear him. So I walk in, and the group is playing, sounding great. But their piano player was just sitting there at the piano, not playing. So without even thinking, I just went up there and asked Art if it was OK if I played. And he said, “Sure.” We finished the set, he came over to me at the piano and hired me on the spot.

I don't listen to a lot of recordings, because there are not too many people whose music I love, but Art was one of them. His music just sounded like music. I don’t really know how to explain it. It’s magical, it doesn’t even have to speak on any level. It was just there, like a “Hallelujah.” He had a sound and that’s how he always sounded, like an orchestra from Africa.

The first concert we did together, on tour in Asia, we’ve gotten through three tunes and suddenly Art stands up and takes the mic, and he says, “And now, ladies and gentlemen, our piano player is going to play a solo piano piece of her choosing.” And that was pretty much how I learned how to play solo piano. I mean, he was crazy, but I was as crazy as he was. That’s why we connected.

After one gig, I was in my hotel room listening to Miles Smiles, and Art came by and just sat and listened. For the next three nights, he played exactly and everything that Tony Williams played on the album — note for note — on the bandstand. He had an incredible mind.

Back then, he used to label people with different nicknames. He used to call me his “adopted daughter,” which was interesting, because my father’s name was Art. I lived my whole life rarely telling people what I thought about anything, because my life was so diverse, so different from anybody else’s. That's why, when I listened to Art, everything he said sounded like he was indeed my father. It was everything I imagined having in a friend, and he saw that right away. He could see things. He was a visionary.

Bobby Watson: “He got to those drums and went somewhere else. And we were either going to go with him or get left behind.” Photo: John Abbott.[/caption]

My friend Curtis [Fuller] used to have this gig in Storyville [in Boston], and one night Art came down to hear me. It happened to be Art’s birthday. He comes down, buys some champagne and sits down to listen. Next thing I know, him and Butch [Miles], who was the drummer, trade sticks and places while the music is still playing. Suddenly, I feel this change in the beat behind me. It was like going down the highway doing 60, and a big semi-truck comes up behind you and nudges the car doing 70. He took me to the men’s room by the arm after that and asked me to join The Jazz Messengers.

I was 24 years old when I joined Art’s band. He taught me how to read the audience, which in turn helped me program my set. He taught me to understand the curve of a set. He taught me how to pace my solos, how to build them, how to shape them. He also told me how to deal with the public, how to be an artist, etiquette, things like that. He taught us how to dress.

The bandstand was Art’s alter. It was his sanctuary. No matter how much went down during the day, he left all his daily trouble, all his emotions, at the edge of the bandstand. And when he walked onto that bandstand, that was sacred ground. He got to those drums and went somewhere else. And we were either going to go with him or get left behind. He may have limped onto that stage, but once sat behind the drums, his posture would become erect; his eyes would light up. And when he'd start playing, he would uplift his own soul, make himself happy. And then he’d make everybody else feel it. Because no matter how tired or angry we were, when he got there and he just set the pace by his spirit, we just went along with it.

To this day, when I go onto the stage, that's my sanctuary and my alter. That’s sacred ground. Art taught me that.

Bobby Watson: “He got to those drums and went somewhere else. And we were either going to go with him or get left behind.” Photo: John Abbott.[/caption]

My friend Curtis [Fuller] used to have this gig in Storyville [in Boston], and one night Art came down to hear me. It happened to be Art’s birthday. He comes down, buys some champagne and sits down to listen. Next thing I know, him and Butch [Miles], who was the drummer, trade sticks and places while the music is still playing. Suddenly, I feel this change in the beat behind me. It was like going down the highway doing 60, and a big semi-truck comes up behind you and nudges the car doing 70. He took me to the men’s room by the arm after that and asked me to join The Jazz Messengers.

I was 24 years old when I joined Art’s band. He taught me how to read the audience, which in turn helped me program my set. He taught me to understand the curve of a set. He taught me how to pace my solos, how to build them, how to shape them. He also told me how to deal with the public, how to be an artist, etiquette, things like that. He taught us how to dress.

The bandstand was Art’s alter. It was his sanctuary. No matter how much went down during the day, he left all his daily trouble, all his emotions, at the edge of the bandstand. And when he walked onto that bandstand, that was sacred ground. He got to those drums and went somewhere else. And we were either going to go with him or get left behind. He may have limped onto that stage, but once sat behind the drums, his posture would become erect; his eyes would light up. And when he'd start playing, he would uplift his own soul, make himself happy. And then he’d make everybody else feel it. Because no matter how tired or angry we were, when he got there and he just set the pace by his spirit, we just went along with it.

To this day, when I go onto the stage, that's my sanctuary and my alter. That’s sacred ground. Art taught me that.

“There were no music stands, no charts, no rehearsal. It was sink or swim. You either knew the book or you didn’t. And that was an incredible learning experience for me.”[/caption]

I was a student at the University of Hartford in the late ’80s, and one year I was back at home in Binghamton when I got a call from my old teacher Jackie McLean. He said, “Steve, call this number,” and he gave me a 212 number. He said, “Buhaina’s looking for you, man.” So I call the number. After the phone gets passed around four or five times, I finally hear Blakey’s voice. He said he needed me that night at Sweet Basil. He says, “Can you make it?” Now, I’m in Binghamton, like three hours away from the city, and it’s the middle of the afternoon. But of course, I say, “Yes!” I had to get there somehow.

Now, Frank Lacy, the great trombonist, was still in the band. This was how Art liked to do things. He would bring someone in on the same instrument just to see what happens. I tried to keep my mouth shut and play what I could play. There were no music stands, no charts, no rehearsal. It was sink or swim. You either knew the book or you didn’t. And that was an incredible learning experience for me.

My first trip to the West Coast ever was with The Messengers. It was a few months after I joined the band. We get to Catalina's in L.A. It's the first night. Freddie Hubbard is sitting at a table directly in front of me, because he lived out there and wanted to see his old buddy Art Blakey. I’m scared to death but thrilled at the same time. We played the first set, and everything went pretty well. We come off the bandstand and Art comes off the drums. He puts his arm around me — he didn’t show me up in front of everybody, he just pulled me aside — and whispers in my ear, “You make your statement, you build to a climax and you get the ‘bleep’ out. Simple, right?” I say, “Yeah, Art.” He says, “Well, do it then!” And then he walked away! (laughs)

That stayed with me, man. I could have hung my head, I could have felt sorry for myself, but no, I wasn’t feeling that way at all. It was very direct and very genuine. And I just knew that I never wanted to hear that again. But Art was always very encouraging. It wasn’t always hard, tough stuff. I wouldn’t trade those experiences for the world. Being a Jazz Messenger, I’m just so proud and honored to be part of that lineage.

“There were no music stands, no charts, no rehearsal. It was sink or swim. You either knew the book or you didn’t. And that was an incredible learning experience for me.”[/caption]

I was a student at the University of Hartford in the late ’80s, and one year I was back at home in Binghamton when I got a call from my old teacher Jackie McLean. He said, “Steve, call this number,” and he gave me a 212 number. He said, “Buhaina’s looking for you, man.” So I call the number. After the phone gets passed around four or five times, I finally hear Blakey’s voice. He said he needed me that night at Sweet Basil. He says, “Can you make it?” Now, I’m in Binghamton, like three hours away from the city, and it’s the middle of the afternoon. But of course, I say, “Yes!” I had to get there somehow.

Now, Frank Lacy, the great trombonist, was still in the band. This was how Art liked to do things. He would bring someone in on the same instrument just to see what happens. I tried to keep my mouth shut and play what I could play. There were no music stands, no charts, no rehearsal. It was sink or swim. You either knew the book or you didn’t. And that was an incredible learning experience for me.

My first trip to the West Coast ever was with The Messengers. It was a few months after I joined the band. We get to Catalina's in L.A. It's the first night. Freddie Hubbard is sitting at a table directly in front of me, because he lived out there and wanted to see his old buddy Art Blakey. I’m scared to death but thrilled at the same time. We played the first set, and everything went pretty well. We come off the bandstand and Art comes off the drums. He puts his arm around me — he didn’t show me up in front of everybody, he just pulled me aside — and whispers in my ear, “You make your statement, you build to a climax and you get the ‘bleep’ out. Simple, right?” I say, “Yeah, Art.” He says, “Well, do it then!” And then he walked away! (laughs)

That stayed with me, man. I could have hung my head, I could have felt sorry for myself, but no, I wasn’t feeling that way at all. It was very direct and very genuine. And I just knew that I never wanted to hear that again. But Art was always very encouraging. It wasn’t always hard, tough stuff. I wouldn’t trade those experiences for the world. Being a Jazz Messenger, I’m just so proud and honored to be part of that lineage.

Ralph Peterson: “I would cut classes to follow this group around — it’s a wonder I even got my degree — but I understood that the education I was getting from watching Art couldn’t be learned in a classroom.”[/caption]

I first met Art Blakey at the Jazz Forum on Bleeker Street. [Trumpeter] Terence Blanchard and I were in college together at Rutgers, and so when he got the Jazz Messengers gig, I would start following the band. I would cut classes to follow this group around — it’s a wonder I even got my degree — but I understood that the education I was getting from watching Art couldn’t be learned in a classroom. I used to like to sit right up under him. I would go up to tables of two of people I didn't know and ask to sit there with them.

One night, I go to Mikell’s jazz club uptown and Wynton [Marsalis] is there, and he re-introduces me to Art Blakey. I got to sit in with Art that night, along with Cindy Blackman, Jeff “Tain” Watts and Marvin “Smitty” Smith. I think for my tune we played “Birdlike,” or one of the easier tunes, but I was prepared to play anything. My job was to make as good of an impression on Art as possible. But the real moment happened as Art was heading back to the bandstand. I kicked off the cadence for “The Theme,” which was how The Jazz Messengers used to close their shows. I had all the breaks, time and tempo changes, the slide into the New Orleans feel, the double-time on the bridge with the break at the end. I had it down. Art ran with that, catting it up in front of the bandstand, like, “What am I supposed to do with this cat playing all my stuff?”

The following March — March of 1983 — he called me up to do the Boston Globe Jazz Festival with the big band, the one with two drummers. And after that, I became “the guy” people would call if they wanted to put a Blakey program together. You see, what’s unique about my relationship with Art is that I was really keen on emulating him. At my stage of development when I was a student, I was in touch with how much I didn’t know about jazz drummers. I wasn’t looking for my own voice; I was content to be teased by the cats in New York when they called me “Baby Bu.” Because as long as I was a “Baby” version of somebody who was swinging, and that was respected, I didn’t give a shit whose “Baby” I was. I think we confuse a lot of young musicians now by robbing them of that process of assimilation, because we don’t encourage imitation. You gotta play some other people’s songs so that you learn your way around the instrument. That’s the process, and that was Blakey’s whole thing.

Art Blakey was one of the most important bandleaders in American music. He did it for 50 years, and the number of bandleaders that emerged from his band is astounding. And not just people who can slap their names on an album cover. I'm talking about musical conceptualists. Leaders of music and men.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cv9NSR-2DwM

Ralph Peterson: “I would cut classes to follow this group around — it’s a wonder I even got my degree — but I understood that the education I was getting from watching Art couldn’t be learned in a classroom.”[/caption]

I first met Art Blakey at the Jazz Forum on Bleeker Street. [Trumpeter] Terence Blanchard and I were in college together at Rutgers, and so when he got the Jazz Messengers gig, I would start following the band. I would cut classes to follow this group around — it’s a wonder I even got my degree — but I understood that the education I was getting from watching Art couldn’t be learned in a classroom. I used to like to sit right up under him. I would go up to tables of two of people I didn't know and ask to sit there with them.

One night, I go to Mikell’s jazz club uptown and Wynton [Marsalis] is there, and he re-introduces me to Art Blakey. I got to sit in with Art that night, along with Cindy Blackman, Jeff “Tain” Watts and Marvin “Smitty” Smith. I think for my tune we played “Birdlike,” or one of the easier tunes, but I was prepared to play anything. My job was to make as good of an impression on Art as possible. But the real moment happened as Art was heading back to the bandstand. I kicked off the cadence for “The Theme,” which was how The Jazz Messengers used to close their shows. I had all the breaks, time and tempo changes, the slide into the New Orleans feel, the double-time on the bridge with the break at the end. I had it down. Art ran with that, catting it up in front of the bandstand, like, “What am I supposed to do with this cat playing all my stuff?”

The following March — March of 1983 — he called me up to do the Boston Globe Jazz Festival with the big band, the one with two drummers. And after that, I became “the guy” people would call if they wanted to put a Blakey program together. You see, what’s unique about my relationship with Art is that I was really keen on emulating him. At my stage of development when I was a student, I was in touch with how much I didn’t know about jazz drummers. I wasn’t looking for my own voice; I was content to be teased by the cats in New York when they called me “Baby Bu.” Because as long as I was a “Baby” version of somebody who was swinging, and that was respected, I didn’t give a shit whose “Baby” I was. I think we confuse a lot of young musicians now by robbing them of that process of assimilation, because we don’t encourage imitation. You gotta play some other people’s songs so that you learn your way around the instrument. That’s the process, and that was Blakey’s whole thing.

Art Blakey was one of the most important bandleaders in American music. He did it for 50 years, and the number of bandleaders that emerged from his band is astounding. And not just people who can slap their names on an album cover. I'm talking about musical conceptualists. Leaders of music and men.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cv9NSR-2DwM